Long before the Greek alphabet carved its way into history, the Linear B script whispered the earliest form of the Greek language onto clay tablets.

These syllabic impressions, hidden for centuries in the ruins of Mycenaean palaces, held secrets of a vanished world—until a twentieth-century decipherment gave voice to the lost language of Mycenaean bureaucrats, scribes, and kings.

The Linear B script was not poetry or philosophy, but the cold and precise language of administration—and through it, the Mycenaean civilization left behind a legacy more enduring than stone.

The Linear B script emerged in the Late Bronze Age, around 1450 BCE, adapted from the still-undeciphered Linear A used by the Minoans. While Linear A may have served ritual or commercial purposes in Crete, Linear B took root in the mainland palatial centers—Mycenae, Pylos, Thebes—and in Knossos, where it replaced Linear A after the Mycenaean takeover.

Its use extended until around 1200 BCE, when the palatial societies collapsed during the wider Late Bronze Age crisis. This collapse extinguished not just political structures but also writing itself—Linear B vanished, and writing would not reappear in Greece until centuries later with the rise of the Greek alphabet.

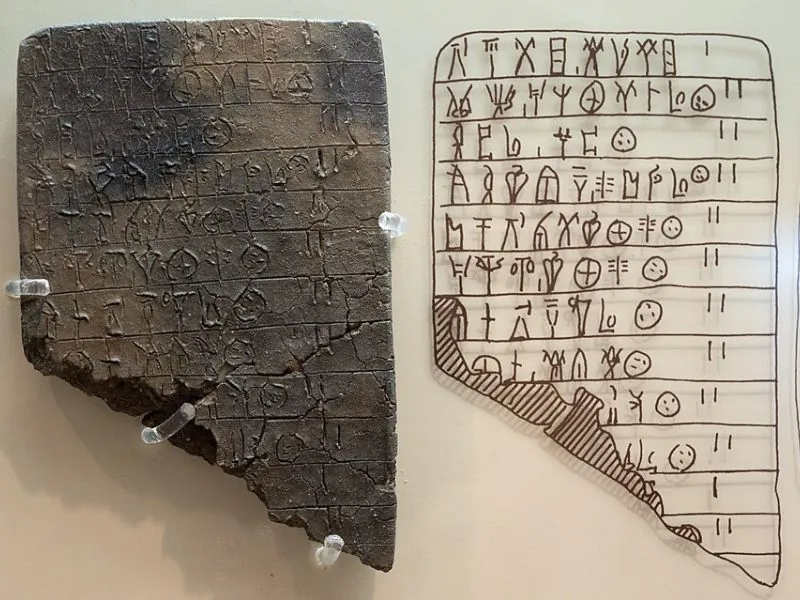

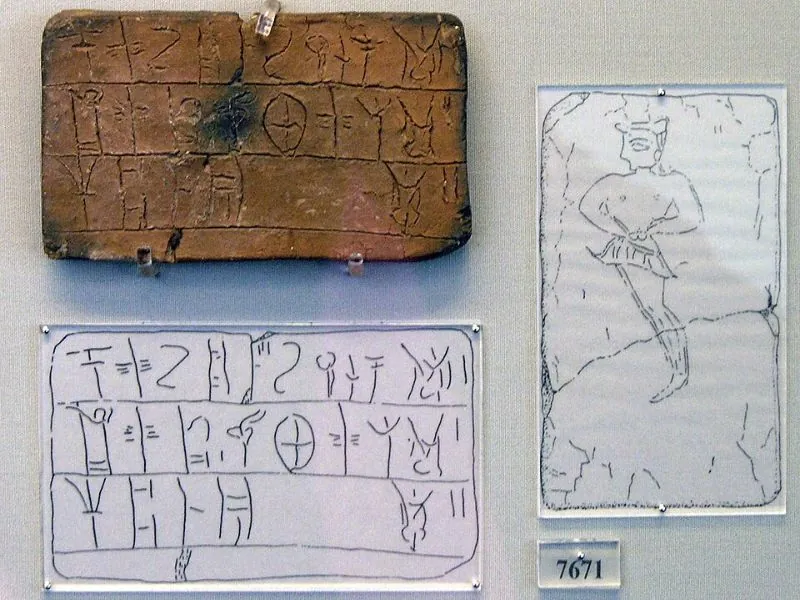

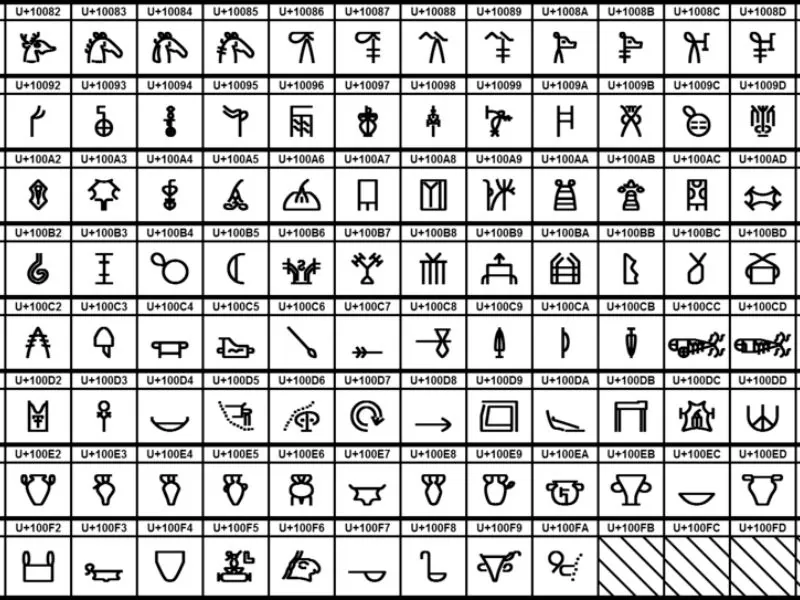

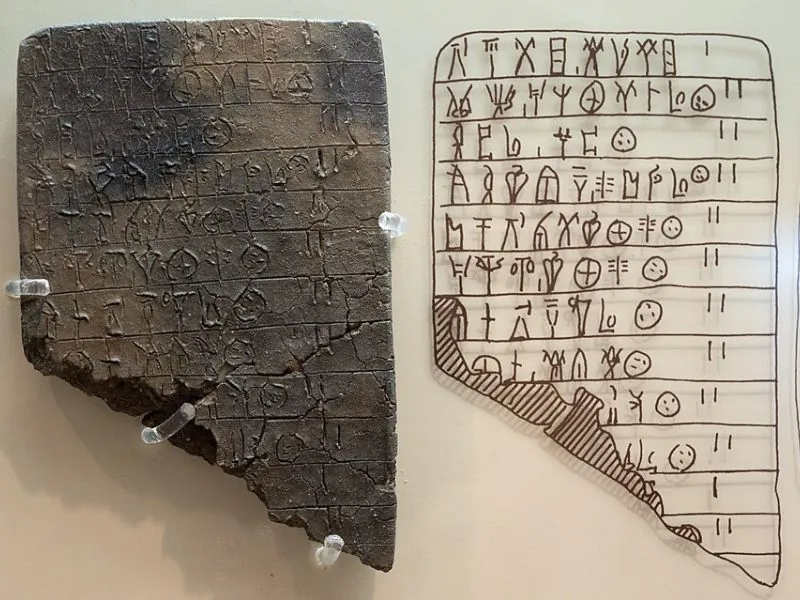

The Linear B script consists of two primary elements: approximately 87 syllabic signs representing phonetic syllables, and over 100 ideograms—visual signs representing commodities, animals, or objects. The syllabic signs recorded spoken elements, but the writing system lacked symbols for consonant clusters or terminal consonants.

This meant that the script offered only a rough approximation of spoken Greek. Ideograms, on the other hand, had no phonetic value.

They were used primarily in economic contexts: denoting quantities of wine, sheep, textiles, or chariots, for example. Though visually stylized and simplified, these ideograms were crucial to the function of the tablets as inventory records.

Far from being literary or narrative, the Linear B script served a strictly administrative function. It was the tool of palatial bureaucracy, used by a trained minority of scribes to record the movement of goods, religious offerings, rations, land ownership, personnel lists, and tax contributions.

Each palace likely had a central archive, with thousands of tablets compiled for seasonal audits and redistributions. At Pylos alone, scholars have identified the hands of 45 individual scribes. Linear B tablets record everything from allocations of oil to descriptions of sacrificial animals.

Once these palaces burned—often catastrophically—the clay tablets were unintentionally fired and preserved, offering us their administrative precision from the ashes.

The collapse of the Mycenaean palace system around 1200 BCE brought a sudden end to the use of Linear B. With the loss of centralized power came the disappearance of writing itself. No new tablets appear after the destruction layers, and for several centuries, Greece entered the so-called Dark Ages—without writing, monumental building, or organized recordkeeping.

This cultural silence obscured the script’s existence until its modern rediscovery and left scholars to debate the nature of Mycenaean civilization through archaeology alone—until Linear B returned to light.

The breakthrough came during the twentieth century. Arthur Evans unearthed the first major cache of Linear B tablets in 1900 at Knossos.

He recognized them as distinct from the pictorial Linear A, naming the new system “Linear B.” For decades, the script resisted all decipherment—until Alice Kober laid the analytical groundwork by identifying grammatical patterns.

It was the architect and amateur linguist Michael Ventris who, in 1952, finally deciphered Linear B, proving it to be an archaic form of Greek. His discovery, supported by philologist John Chadwick, stunned the academic world: Greek had been written centuries earlier than previously believed.

The decipherment of the Linear B script redefined the origins of Greek literacy. It proved that the Mycenaean world was not simply pre-Greek or proto-Greek—it was part of the Greek linguistic continuum. This revelation helped historians reconstruct the economic structure, religion, and political organization of the Late Bronze Age.

The scribes who etched out records of wine, wool, and sacrifice unknowingly preserved the oldest form of Greek in existence. Today, Linear B stands as a fragile but powerful testament to the bureaucratic sophistication and linguistic depth of the Mycenaean world—a voice from clay that still speaks across millennia.

The Linear B script is more than a historical artifact—it is a linguistic bridge from the mythical age of Agamemnon to the written legacy of Homer. Silent for centuries and then suddenly understood, it changed what we know about early Greece.

Though it spoke only in ledgers and lists, its syllables echo with the first written sound of the Greek language—a language destined to shape the Western world.